Business continuity (BC) and disaster recovery (DR) are not the same thing, although there are some common characteristics. A BC plan is designed to include all departments in a company, but a DR plan is often focused on restoring the IT infrastructure and related data.

“A disaster recovery plan is an essential IT function and if not in place could result in company bankruptcy or severe reputational damage when data cannot be restored”, Przemysław Jarmużek, technical support specialist at SMSEagle. The financial costs involved are just another factor, he added.

What elements of a disaster recovery plan cannot be omitted? What’s the purpose?

Few company owners are psychics but things like insurance and DR plans reduce company risk, providing a framework for companies that allows rapid recovery of data and/or replacement of key hardware/software components.

Know your Network

Your company network administrator must have more than a fair idea of the software and hardware that are currently part of your network. Therefore, an ongoing inventory list is essential, most of which can be achieved by using network monitoring and auditing tools. These will allow a comprehensive list of computers connected to your network and the software on each. Note that license management is another part of this inventory control process and additional hardware is also added where appropriate. This additional hardware could include multifunction printers, hubs or routers and anything else that is needed for network functionality. Consider this inventory as your shopping list when disaster strikes. It is also worth noting which items have a long lead time (servers, for example). Creating an inventory of spare parts is a good idea and could save the day when disaster strikes.

Know your Disasters

It is pointless to instil fear in company owners about impending disasters. They are as aware of the risks as we are. Each company will have its own risks. Many of these risks are directly linked to its location, whether extreme weather conditions, risks of flooding, forest fires or loss of essential services and equipment. These are the most obvious, but to lapse into management-speak briefly, why not think outside the box?

Even the Pentagon has used a hypothetical zombie apocalypse to test their response methods and maintain a working government under these conditions. Consider alien invasions and any other scenario that could conceivably or inconceivably shut down company operations. How long would it take to resume work if each scenario happened?

If your company can continue operating during a zombie apocalypse (when essential services are down) then yours is truly a robust DR plan.

Now What?

What actions will you take for each disaster type? Obviously, if there is a flood scenario, the aim is to protect equipment again water damage. Perhaps placing all equipment high above the floor is a solution but how high is necessary? Given that you have drafted a list of possible and impossible scenarios, make sure that your solutions to each one is well documented, logical and possible at short notice. Bite the bullet and purchase or modify the equipment necessary to protect your IT infrastructure.

Unfortunately, not all water damage is caused by flooding, perhaps a water tank leaks through the ceiling of your server room and casually destroys the server, firewall and 24-port hub before you can move the server rack. How long will it take you to restore the server and network? Do you have a spare server, firewall and hub? In this scenario, a company is caught unprepared, unaware that water is stored above their equipment. Know where all water is stored and dispersed throughout your building and avoid such problems.

From this simple example, you must focus on minimising risk in as many areas as possible.

Tactical Teams

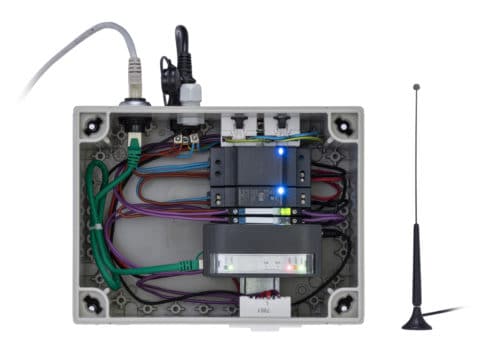

When a disaster happens, the priority is to make sure that all employees are safe and to inform them of current events. Once this task is completed, who leads the disaster response? When a disaster occurs, it is too late to leap into action, assigning responsibilities on the spot. Responsibilities and tactical team members must be assigned as part of the DR plan. In addition, if zombies eat your designated team leader, then the backup must take over. Define employee responsibilities and have backups in place in case they are delayed or incapacitated. This last item is perhaps the most important. However, to be most effective, any interruption in network service should generate an alert to multiple DR team members. This is often achieved by cost-effective (and self-powered) network monitoring devices that utilise a GSM/3G network to send SMS messages and emails as soon as network traffic stops.

In conclusion, while the above lists the key elements of any successful disaster recovery plan, it is also worth noting that an untested plan is less than useless. Test your DR plan during off-peak hours to ensure it will work when needed. Test how long it takes to restore all your data from backup. Such activities will ensure that if the worst happens, you and your company will emerge unscathed to resume your company operations.